Hike Your Own Hike: One Woman's Solo Journey on the Appalachian Trail

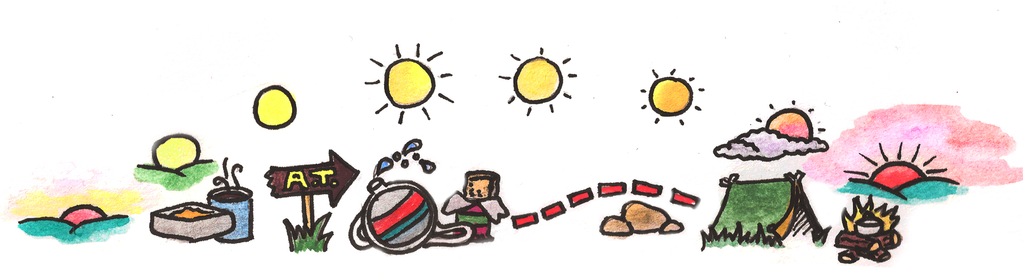

/Story by Sandra Davidson Photos from the Trail by Sarah Acuff Portraits by Baxter Miller Illustrations by Cameron Laws

"Often times, people assume I didn't do it alone. They don't assume, from first onset, that I did it solo as a woman. But when they realize that, it stumps them a little bit... they don't really know where to go from there."

From May 1, 2014, to July 28, 2014, Sarah Acuff, of Carrboro, North Carolina, hiked over 700 miles of the Appalachian Trail, alone. She was 24.

I met with Acuff on a cool, humid April morning several weeks ago in the Carrboro bungalow she is renting with four other people. Over a freshly brewed cup of French-pressed coffee, she shared the story of her journey, which began three years prior to the hike.

In the summer of 2011, Sarah Acuff was bitten by a tick. At the time, she was working as a rock-climbing instructor at Shiloh Quaker Camp, an outdoor camp an hour north of Charlottesville, Virginia, just outside the Shenandoah National Park. The bite occurred late in the summer between her junior and senior year of college at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, where Acuff was studying Political Science and Global Studies. She vaguely remembers a coworker noticing the tick on her back and pulling it off. The incident, which she has now pinpointed as the day she contracted Lyme disease, was largely unremarkable.

As camp ended, Acuff returned to UNC to resume her studies. She had two semesters of coursework left to graduate, and she planned to do that on time. She had always been a good student, engaged in campus activities within and beyond the classroom, but that fall, Acuff found it difficult to resume her normal campus life. "If I went to the gym or did anything like [go] for a run, I would need to take a couple of days off because I was really tired," said Acuff. "I would need to sleep like 12-14 hours a night, and I wouldn't feel reseted after that." Her fatigue was coupled with unprecedented occurrences of panic attacks, and eventually depression.

At first, Acuff attributed this health shift to typical senior stress and began visiting Campus Wellness for counseling where she was treated for anxiety with antidepressants. She powered through the next two semesters of school constantly wondering, "Why can't I do the things I used to do?" Coursework that once came easily was difficult, and her struggle in class caused her to need an additional semester to graduate. The following summer, she returned to camp, but her health did not improve. She returned to UNC in the fall of 2012 for what was supposed to be her final semester of class. After a week in class, Acuff withdrew, and in September she took a job with REI. She hoped removing the stress of school would alleviate her symptoms. Weeks later, her health continued to deteriorate.

Unbeknownst to her at the time, Acuff was suffering from Lyme disease, a disease spread through a tick bite that can cause difficulty sleeping, muscle and joint pain, and fatigue. Undiagnosed Lyme disease may have psychological ramifications for those who experience a seemingly unexplained swift decline in health.

In September 2012, Acuff could no longer dismiss her health issues. During a six mile hike near Falls Lake with REI staff, Acuff's joints stiffened, her body began to ache, and she began experiencing tunnel vision. The event frightened her. She remembers, "I knew stress couldn't be the real reason anymore. I knew something else was wrong." She reached out to her doctor from summer camp, Cathryn Harbor, who immediately ordered a blood test. Acuff drove to a Greensboro lab for the test, then waited.

The test result came back as "equivocal," meaning a definitive diagnosis could not be made. The results did, however, reveal the presence of long-term antibodies to the borrelia bacteria which causes Lyme disease. Despite the equivocal results, Sarah's doctor agreed to treat her as if she had a definitive diagnosis, and she began a six-month antibiotic treatment regimen.

Sarah explained to me, "Lyme disease threw a wrench in my five-year plan."

The notion of a five-year plan had been an important part of her upbringing and life as a young adult. Raised in Charlotte by her mother, Andria Krewson and grandmother, Nancy Krewson, Acuff's father was not a part of her life. Being able to juggle many roles and responsibilities, regardless of gender expectations, was a part of her daily life. Acuff explained to me, "Growing up, I don't think I was ever told that I couldn't do something, but there were things I was told I should do in order to be a good daughter." Doing well in school, graduating from college, and finding a good job were integral parts of that equation.

As her body healed, Acuff began reimagining what her future could be. Lyme freed her of those long-held expectations and forced her to think about other things she could do. Acuff had become an avid outdoors woman after starting college and, for years, she'd dreamt of hiking the Appalachian Trail. Though, she always suspected she'd do that after retirement or when she was financially stable, at least. While recovering from Lyme, she needed something to look forward to. She decided hiking the Appalachian Trail would be that thing. Acuff said, "I wanted to get my body to a place where it had been before, and also test myself and get to know really intensely what exhaustion felt like without having Lyme."

In the Fall of 2013, after months of treatment, Acuff began planning the hike. Over the next nine months, she learned as much as she could about hiking the trail from studying Trail manuals and from coworkers at REI. A friend initially showed interest in joining her but dropped out. She forged ahead, committed to doing the hike in the summer of 2014, even if it meant doing it alone.

I asked Acuff how she felt about doing the hike alone. She said, "It would have been great to have somebody along, but I didn't want to postpone a really cool experience for something that wasn't necessary for the experience to be good. If you wait around for the perfect circumstances or perfect trip, you find yourself years down the road [wondering] what have [you] done with these years." And Acuff, an only child, was used to solitude.

On May 1, 2014, Acuff's mother drove her to a parking lot, one mile north from the summit of Springer Mountain in Georgia, the southern terminus of the trail. They hiked the first mile of the trek and camped together that evening. The next morning Acuff said goodbye. Then and there, Acuff began her journey alone.

The trail snakes its way along the Appalachian Mountain Range which begins in Georgia and extends through Maine, touching North Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia, West Virginia, Maryland, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Vermont and New Hampshire along the way. The Appalachian Trail Conservancy estimates the foot trail is 2,180 miles long, with 15,524 recorded hikers having completed the full trail since 2010, only 25% of which were women. Adventurers have been able to hike the trail since August of 1937.

Acuff set out to complete the entire trail. For two and a half months, she carried a 35-pound bag of provisions on her back. She filtered her own water. She ate a lifetime's worth of instant breakfast, Cliff Bars, grain mush (noodles, rice, ramen), dehydrated meals, salmon and tuna. She slept in a hammock instead of a tent, which landed her the trail nickname "Charlotte's Web" (she is originally from the Queen City). She encountered several bears, that she describes as, "not too scary." She met an array of interesting characters along the trail: mostly middle-aged men but also three women hiking the trail solo, out there for any number of reasons.

She began her trip slowly, but by the end of the journey averaged between 12 and 17 miles a day depending on the terrain. Her trip took her through the Rhododendron filled section of Southwest North Carolina; through a 3,500 foot vertical grade near the Nantahala National Forest; through the wild pony wonderland of Mt. Rogers in Grayson Highlands, Virginia; and through the supportive, funky trail town of Waynesboro, Virginia, near the southern terminus of the Shenandoah National Park, home to a hiker's pavilion with solar panels on the roof for charging electronics and a hiker box with donated or free gear and food for hikers.

Her mother, like most would be, was worried about Sarah being on the trail alone. She recalls feeling, "Fear, concern, and a little joy that she was going to be able to see some of the most beautiful places in North Carolina and the South." Krewson thinks, "being a soccer mom in earlier years prepared me for this support role. You have to make sure they stay hydrated and fed, and let them do this physical thing and support them how you can."

And she did. Every few days, Krewson visited her local post office to ship a care package with food and supplies to the next trail town Sarah was headed towards, and she visited Sarah to hike on several occasions. Sarah explained, I think it was important for her to come along the way..because it was such a cool experience for me that I wanted to share with her, and [I] also proved to her that I was okay. If I can do something that hard... I can do a lot."

The first few weeks of the hike were the most challenging. Acuff struggled to get her trail legs and pushed through the discomfort of achy hips and low back. After three weeks on the trail, she found herself suffering from extreme fatigue. Scared her Lyme disease had returned, she left the trail at mile marker 317.4 for medical attention. A blood test revealed everything was okay and it was likely that she hadn't been eating enough to replenish her body after the long hikes. She returned to the trail to continue.

Acuff grew accustomed to the solitude, which inherently allowed her to confront some personal demons that arose from her struggle with Lyme disease: why did she go so long without seeking further medical treatment? "I felt like to some extent I'd recognized something was off, but I chocked it all up to senior stress basically, or changing life circumstances when you're 22. The confluence of all that led me to steamroll ahead. I [was] more willing to tear myself down before [stopping] before a goal was reached."

In the months following her diagnosis, Acuff had been angry and disappointed that she'd let herself get and stay so sick without seeking help. The trail gave her the chance to face that. She explained to me, "When your mind and body are so tired that they can't fight each other anymore, that internal dialogue where you get to self-protect in a way or not get too deep [or] focus on not having to sit with yourself--you can get pretty deep and go past certain point in your thought processes that can be really amazing and that completely shift how you see circumstances. I got the chance to do that [on the trail] because my mind was so exhausted I stopped fighting myself."

Stepping off the trail for medical treatment was a personal victory for Acuff. "That's why I was out there. To get in touch with what felt wrong and what felt right. I wanted to know and pay attention to that, and respond to that." Sarah continued to respond to what she wanted and needed. In the beginning, she had set out to complete the whole trail that summer, but after a week off the trail volunteering at the camp she'd worked at in years past, she decided to get off the trail. Her journey concluded on July 28, 2014 at Little Stony Mountain, the cliffs where she'd taught rock-climbing four years earlier.

She was not disappointed she didn't complete the entire trail. "I pretty much know that I can do a lot because of just having sat with myself, and lived with myself, and carried everything I needed on my back," said Acuff. It's an experience she would "give nothing else for."

Acuff says the only time she was scared on the trail was when a brazen young bear crept close to one of her campsites. I offered that I feel our society doesn't encourage young women to take trips like this, and she nodded in agreement, but added, "I didn't go into it wanting to martyr myself for all the women who are out there. It was more about being confident in my own abilities regardless of who I was with. Being confident in my own resources, my own abilities to problem solve or go with the flow and see what happens. Once you're out there, you can't fight nature."

Acuff's trip gave her confidence and an open mind about her desires and wishes for the future. She's made a full recovery from Lyme disease. She is working to finish her degree this summer and is currently planning for a large hike in Iceland for August. She hopes to make her way to the Appalachian Trail this summer to leave trail magic (food and beverage goodies) along the way for exhausted hikers.

I asked Acuff what her biggest take away from the hike was and will leave you with her words:

"If you hike for other people, there is a saying out there that you'll hear from a bunch of different places- but hike your own hike. The idea that [you should] go as fast or as slow as you want... just be out there. Experience it for what you want out of it. Everyone is out there for a different reason, and everyone enjoys it in a different way. You can't judge anyone else's hike, and they can't judge yours. Know what you need and do what's best for you."